In April I was furloughed from my job and, at first, struggled to get unemployment benefits. But now, in an ironic twist, my problem isn’t getting paid. It’s getting overpaid.

While millions of American’s haven’t gotten unemployment payments, some people like me have the opposite problem: The government is sending us too many checks or direct deposits, money that we’re required to return.

Gannett, my employer and publisher of USA TODAY, said in late March that certain reporters and editors will be furloughed on a rolling basis in the second quarter. The CARES Act created a federally funded Pandemic Unemployment Assistance program that provides unemployment benefits to furloughed workers, who typically aren’t covered under traditional unemployment.

I applied for New York benefits online in late April after my first furlough week, but then I received a message that my application was incomplete and that I needed to call the unemployment office. But I couldn’t get a real person to answer for the next month and kept running into automated messages.

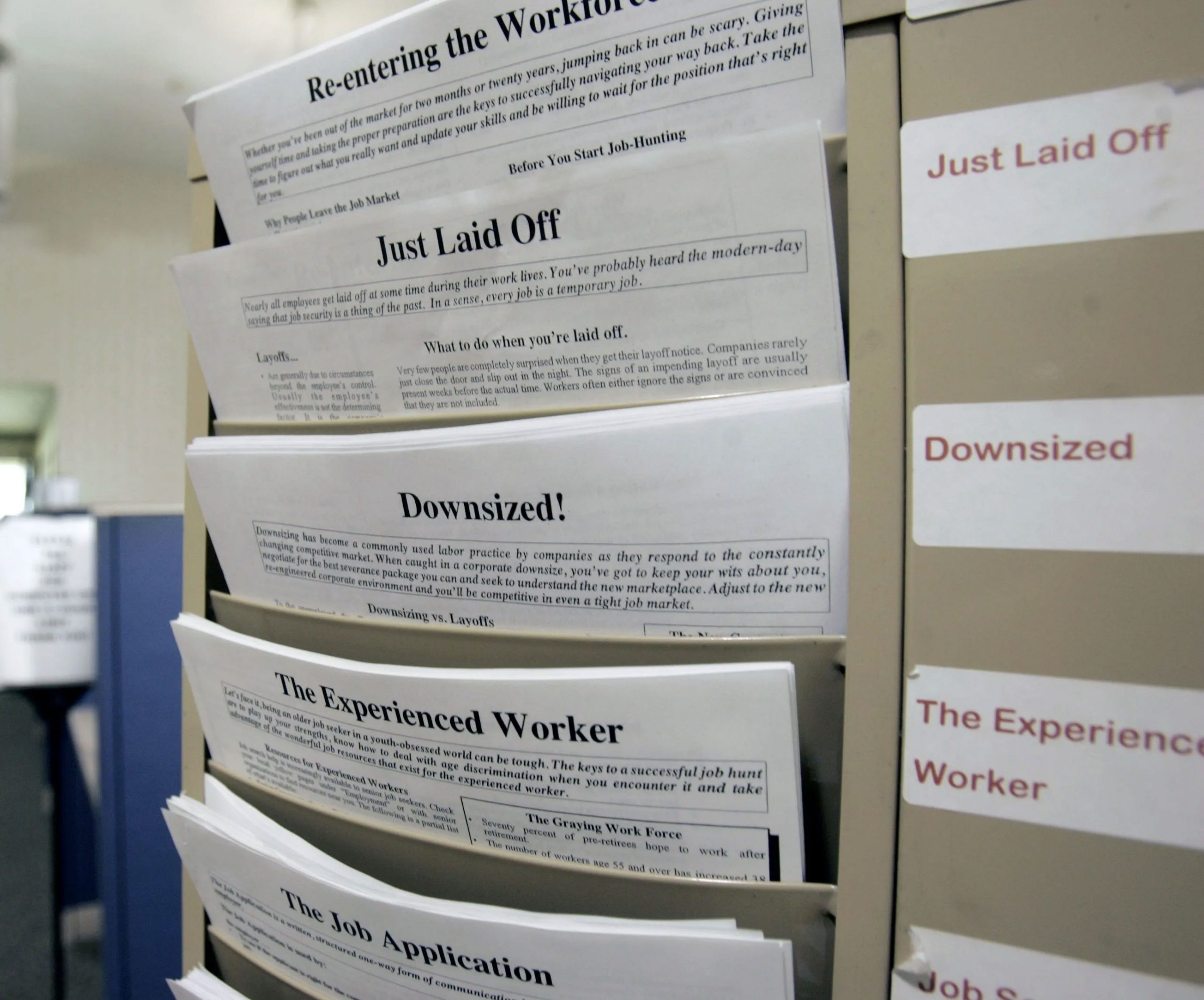

State unemployment systems have been overwhelmed after a record-breaking 42 million Americans filed jobless claims since mid-March as businesses battered by the pandemic laid off and furloughed workers.

After aggressively calling, staying on the line for hours and speaking with multiple people, my application was finally complete. I received my first payment after a few days. But a week later, I checked my bank account and a whopping $4,000 was deposited.

That couldn’t be right. For one thing, I couldn’t even certify my most recent claim because I kept getting error messages online. So I immediately alerted my editor and reached out to the New York Department of Labor.

“Issues like this are extremely rare, and likely occur after a New Yorker improperly submits certifications,” Deanna Cohen, a spokeswoman at the department, said..

She said no one could have predicted the wave of unemployment applications that crashed over the United States because of the pandemic, and every state was struggling, “but New York has moved heaven and earth to get billions of dollars in benefits into unemployed workers’ hands.”

More unemployment overpayments pop up

It’s still unclear how this happened to me. But one thing is certain: I’m not alone. Others have received overpayments across the country, including other Gannett employees in Florida.

Virginia is another state with overpayment problems. In May, the Virginia Employment

Commission notified about 35,000 self-employed people they were overpaid between $600 and $1,200, money that the agency said will be deducted from future checks.

Susan Hiltz of Macomb Township, Michigan, was in the same boat. Hiltz, 60, was laid off in March from Oakland County Sheriff Police Athletic League, a nonprofit organization that provides athletic activities to youths.

She received an email from her state’s unemployment office in May saying they made a mistake and overpaid her about $1,300 in benefits. They caught the issue so fast that she didn’t notice they had made a mistake. It was withdrawn from her bank account and fixed the same day.

“They made an error, found it and corrected it very quickly. I didn’t have to get involved,” Hiltz says. “This is a large amount of money that is being dispersed. I just hope it’s getting to the people that really need it.”

Nena Perez, 44, is one of those people. The single mother, who lives in the Bronx in New York, was forced to file for unemployment in March because she had to stay home to take care of her two youngest children, ages 10 and 13.

Perez, who had previously worked as a home health aid at Health Acquisition, received a series of back payments in April and early May, but the money stopped coming in and no one will answer her calls to the unemployment office for help, she says.

“I’ve gone without eating just to make sure my kids have food,” Perez says. “How are they giving people extra money? Are you kidding me? I can’t even get a week. This hurts.”

Some didn’t know they were overpaid

It hasn’t been as easy for people in other states to return the money. And some people didn’t even know they were overpaid until their state alerted them.

Savannah Fosdick, 24, was furloughed from her job in March at a Starbucks in a Barnes & Noble in Olympia, Washington. She was approved for PUA in April and was paid benefits retroactively. But then the payments abruptly stopped in mid-May.

Washington state then informed Fosdick that she owed nearly $1,200 in overpaid benefits from her current unemployment. Now she can’t get anyone from the unemployment office to answer her calls and she doesn’t know how she’ll afford to return the money, she says.

“I’m freaking out. How was I overpaid when I was approved?” Fosdick asks, adding that the pause in payments has weighed on her financially because she’s also supporting her mother, who is on disability. “My washer is broken. My utility bill is racking up. It’s been really stressful.”

How I sent the money back for New York

In New York, I wasn’t penalized for the error. Those who are overpaid will receive a written notice in the mail, which gives instructions on how to send a check or money order to pay the total amount due, Cohen says.

They didn’t have an option to withdraw the money from my bank account like Hiltz in Michigan.

You can mail a payment for all, or a portion, of the amounts that was overpaid.

For those in other states, don’t spend the money and hold onto the extra payment, experts advise. Contact your state unemployment office and wait for them to notify you by mail on how to pay the money back, they said.

Be sure to pay it back

There are repercussions for not returning overpaid benefits. If it’s deemed fraud, the government could garnish your tax refunds and you could potentially go to jail.

If it’s an accident, it’s technically not fraud and you could potentially fight it to keep the money, according to Laurie Yadoff, an attorney at Coast to Coast Legal Aid of South Florida. But it could be difficult and costly if you need a lawyer, she added, and it eventually catches up with you.

“I wouldn’t be surprised to see more overpayments in the future,” Yadoff says. “Generally, people get the benefit of the doubt. If it wasn’t your fault, it could be waived or you may have to pay it back in installments.”

If you need jobless benefits later, the government may withhold that from you to pay back what you owe. For those on government assistance programs, for instance, if the government deems that there was an intentional violation by giving false information for unemployment, you might not receive food stamps even if you’re eligible, Yadoff cautions.

The CARES Act expanded who was covered by unemployment, allowing self-employed, independent contractors, temporary workers and gig workers to seek benefits, people who previously didn’t qualify under traditional unemployment. That’s potentially created more issues for state unemployment systems, Yadoff says.

She expects to see more overpayment issues moving forward.

“The unemployment system in Florida is erratic,” Yadoff says. “Getting answers is impossible. Before you could call someone. It’s more confusing now.”

Unemployment overpayments will catch up with you

Helena Moyer of Plantation, Florida, ran into overpayment issues after she was forced to file for partial unemployment after her hours as an accountant were reduced at National Marine Suppliers. The 43-year-old mother of three started receiving unemployment in March. But then the money stopped.

After struggling to get someone to answer her calls, she eventually found out that she owed $550 in overpaid payments from 2015. It came as a shock to her since she was never made aware of the issue, she says.

Moyer paid back what was owed, but she still hasn’t received any additional unemployment checks over the past two months because of a glitch in Florida’s online system.

The Florida Department of Economic Opportunity didn’t immediately respond to requests for comment.

“I was shocked and frustrated,” Moyer says, who is worried about how she’ll pay her $2,650 rent next month for a four-bedroom house. “When I can’t pay my bills, what’s going to happen then? Why can’t Florida get it together?”